For those interested in researching 16th century Irish clothing, the following is a comprehensive list of the sources I have found to date.

Books

The first two books in this list are key – I believe they are must haves if you are wanting to learn about 16th century Ireland, and the surrounding time periods and places.

- Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland, published by Batsford. ISBN 071345251X, 9780713452518. This book includes information from the Bronze Age through to the 20th Century, including contemporary quotes and images.

- McClintock, H.F. (1950). Old Irish and Highland Dress and that of the Isle of Man with Chapters on Pre-Norman Dress as Described in Early Irish Literature and of Early Tartans. To my knowledge, this book is out of print and has been for some time. I obtained a second hand library copy through the online AbeBooks site.

—

- Duffy, Sean (editor, 2005). Medieval Ireland, An Encyclopedia. Routledge, New York and London.

- Flavin, Susan (2014). Consumption and Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland, Saffron, Stockings and Silk. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge. ISBN 978-1-84383-950-7.

- Heath, Ian and Sque, David (1993). Men-At-Arms Series, The Irish Wars 1485-1603. Osprey Military. ISBN 1-85532-280-3.

- Hunt, John and Harbison, Peter (1974). Irish medieval figure sculpture, 1200-1600: a study of Irish tombs with noted on costume and armour, Volume 1. Irish University Press.

- Joyce, P.W. (2008). A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland. Dodo Press (publisher). http://www.libraryireland.com/SocialHistoryAncientIreland/Contents.php

- Kelly, Gerald A John (2010). How the Irish and Scots Dressed in the 16th Century. The Druid Press. ISBN 1453869727.

- Richardson, Catherine (2004). Clothing Culture, 1350-1650. Ashgate Publishing Ltd. Chapter Four: Tomb Effigies and Archaic Dress in Sixteenth-Century Ireland by Elizabeth Wincott Heckett, Pp63-76.

- Walker, Joseph C. (1788). An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish. Printed in Dublin. http://books.google.com

- Walker, Joseph C. (1818). Historical Memoirs of the Irish Bards. http://books.google.com

Extant Finds

There are not a large number of clothing finds for 16th century Ireland, however, those I have come across are linked here.

- Moy Gown – is an extant kirtle-like dress that was found in a bog at Moy, County Clare, Ireland. It is housed in the National Museum of Ireland and has not yet been accurately dated, however, is estimated to be from somewhere around the 14th-17th centuries. There are tracings of the remnants of this dress (as well as a modern reconstruction) available on Matilda la Zouche’s Wardrobe.

- Shinrone Gown – is an extant wool dress that is front-laced and high-wasted with hanging sleeves. It was found in a bog near Shinrone, County Tipperary, Ireland and is housed in the National Museum of Ireland. The Shinrone Gown is dated to the second half of the 16th century. A greyscale photo of the extant gown is available online.

- Killery Outfit – is an Irishman’s outfit dated to the late 16th century that consists of a long jacket that hangs to around the mid-calf and some cross-hashed trews. They were found in a bog in Killery, County Sligo, Ireland. Greyscale images of the ensemble are available online.

- Kilcommon Doublet – is an Irishman’s jacket found in Kilcommon Bog in Thurles, County Tipperary, Ireland. It is dated to the 16th-17th centuries and made from a coarsely woven wool. The skirt on the doublet is pleated and it appeared to have hanging sleeves. A greyscale image of the extant jacket is available online.

- Felted Hats – there are three extant Irish hats found in Knockfola (County Donegal), Derrindaffderg (County Mayo), and Tawnamore (County Sligo) in Ireland. Each of them is a different shape, but all are felted and blocked hats dated to the 16th-17th centuries. Images of these hats can be seen in Dunlevy’s Ancient Irish Dress: A History (1989), or online.

- Carnamoyle Stockings – a knitted pair of stockings dated to c1600, housed in the National Museum of Ireland. Photos and the museum analysis of these stockings is available online, published by Lady Angharad (2006).

Watercolours, Drawings, and Woodcuts

Several 16th century artists published manuscripts of watercolours depicting national costumes of a variety of localities around the world. Several of these include depictions of Irish men and women of various status (i.e. from the poor ‘wilde Irish’, to the middle classes, and to the rich noblemen and noblewomen).

In 1788, Joseph C. Walker published An Historical Essay on the Dresses of the Modern and Ancient Irish, which includes sketches of various figures on Irish monuments. On page 46, he included sketches of two figures of Irish women.

Kostüme der Männer und Frauen in Augsburg und Nürnberg, Deutschland, Europa, Orient und Afrika is an anonymous manuscript published c1500 that depicts hundreds of watercolour plates of the national dress of various cultures around the world at the time. Plates 42o, 41r, and 42r depict various Irish soldiers and plate 43o depicts an Irish woman. The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek has made the entire manuscript available online.

Lucas de Heere, a 16th century Dutch artist, documented several Irish fashions of the time. In c1570, he drew a noblewoman, a Burghers wife, an Irish soldier and a ‘Wilde Irishman’.

In around 1575, de Heere published 134 watercolour plates in a manuscript titled Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre avec leurs habits et ornemens divers, tant anciens que modernes, diligemment depeints au naturel par Luc Dheere peintre et sculpteur Gantois (Theater of all peoples and nations of the earth with their clothes and various ornaments, both ancient and modern). Plates 81 to 83 depict between four Irish women, four Irish men and an Irish boy from the 16th century of varying social statuses. These plates are available in high resolution from the University Library of Ghent’s website.

John Speed published a map in 1610 that included colour images of ‘Gentle, Civill, Wilde Irish’ dress. It is available on the Irish Historical Textiles website.

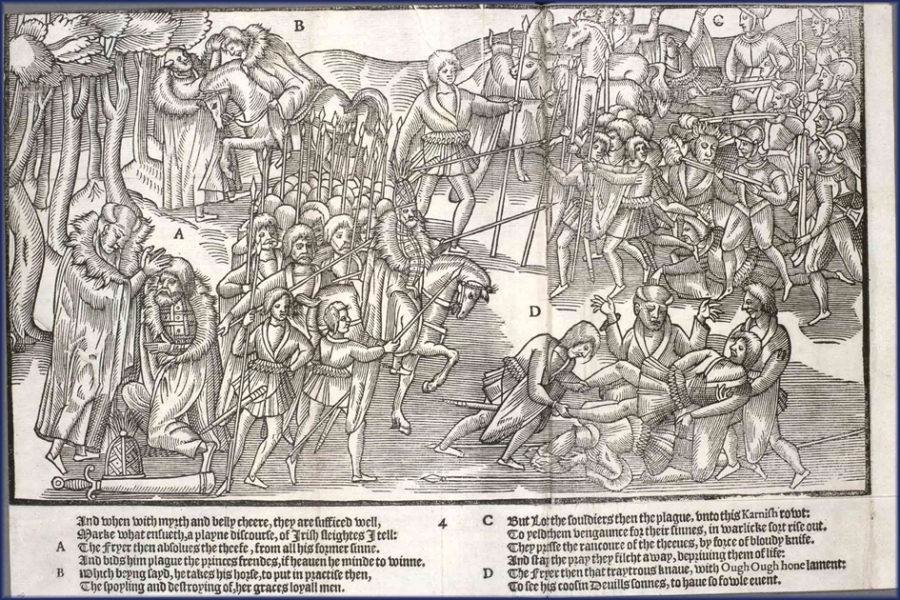

The Image of Irelande from 1581 by John Derrick is a series of woodcuts that depict a number of different Irish people (bards, nobility, soldiers, etc). When looking at these woodcuts, it’s recommended that you do so in the context that this was published as English propaganda against the Irish.

The de Burgo manuscript contains illuminations from Connacht, Ireland, ca. 1578 of soliders.

Contemporary Literature

Thanks to the bright and diverse differences between Irish and English dress in the 16th century, there are many contemporary descriptions available that outline what was being worn by the Irish at this time.

Most of these writings are in the context that the characteristics of the clothing were considered to be odd and different when compared to their neighbours. Some of the sources are accounts from travellers from various European origin, and some are legislative proclaimations (such as those listed earlier). The differences written about are often vary prescriptive and distinctive to Irish wear at the time, making them useful to compare with images from the time.

When thinking about the validity of any given description, however, it is important to consider the context of the writer. Some writers were biased against the Irish due to the various rebellions, wars and hostile takeovers that were occurring at the time.

Again, It is encouraged to compare images from these sources with information and images from other sources to determine how accurate these representations might be.

Excerpts of descriptions such as these can be found in Dunlevy’s Dress in Ireland: A History (1989), and McClintock’s Old Irish and Highland Dress (1950).

Stone Effigies and Tombs

In this context, effigies are stone likenesses of the deceased. These effigies were often atop the burial tomb of those the effigies depicted – typically noblemen and noblewomen (noting that they are usually of English or Norman decent rather than Irish decent). These burial tombs often had ornate carvings around the effigies, providing further images of people and their clothing carved in the 16th century.

When looking at these images, one needs to remember that the clothing and accessories depicted may be purely ceremonial and not an accurate representation of clothing worn at the time. They are also unlikely to represent Gaelic clothing of the time, more likely styled after the English styles. It is encouraged to compare images from these sources with information and images from other sources to determine how accurate these representations might be.

The Trinity College Dublin has an online database called Trinity’s Access to Research Archive (TARA). Searching through this database will allow you to find many high resolution photos of 15th and 16th century Irish tombs and effigies (author Edwin Rae has published many good images there to this affect).

Pinterest Board

I made a pinterest board of pre-17th century Irish images and extant finds that I update from time to time. Each of the images is linked to as close to the original source as I could find: https://www.pinterest.com.au/u4122747/images-of-pre-17th-century-irish-clothing/

Reconstructions

- Carlson, I. Marc (1999-2002). A reconstruction of a Garment from the Moy Bog, Co. Clare, Ireland. http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/moy3.html

- Matilda la Zouche’s Wardrobe (2006). The Moy Gown. https://matildalazouche.livejournal.com/3658.html

- McGann, Kass (2000). Dyeing with real saffron. http://www.reconstructinghistory.com.

- McGann, Kass (2000, 2003). What the Irish Wore: The Shinrone Gown – An Irish Dress from the Elizabethan Age. http://www.reconstructinghistory.com

- Sarnoff, Allison (2006). The Carnamoyle Stockings: A Late 16th Century Textile Mystery.

http://scanorthernlights.org/results/2006/RP-Carnamoyle_Stockings-LadyAngharad.pdf - Shionnach, Ceara (2011). Research Project: 16th Century Irish Attire. https://cearashionnach.wordpress.com/2011-2/research-project-16th-century-irish-attire/

- Shionnach, Ceara (2014). Fencing Jacket – 16th Century Irish Style. https://cearashionnach.wordpress.com/2014-2/fencing-jacket-16th-century-irish-style/

- Shionnach, Ceara (2015). 16th c Irish “Onion Hat”. https://cearashionnach.wordpress.com/2015-2/16th-c-irish-onion-hat/

Other Resources

- Biggam, Carole P. (2006). Whelks and purple dye in Anglo-Saxon England. The Archaeo+Malacology Group Newsletter, Issue 9, Pp1-2.

- Irish Archaeology (2013). 16th century images of Irish people.

http://irisharchaeology.ie/2013/12/16th-century-images-of-irish-people/ - Matsukaze Workshops (19/06/2014). 16th Century Irish Dress. http://matsukazesewing.blogspot.com/2014/06/16th-century-irish-dress_19.html

- Nicolson, Adam (1995). Life in the Tudor Age. Reader’s Digest. Pp 38-39, 71, 85.

- NZICFR (New Zealand Institute for Crop and Food Research Ltd, 2003). Growing Saffron – the world’s most expensive spice. Crop and Food Research, No. 20, August 2003, Pp1-4.

- Rae, Edwin C. (1971). Irish Sepulchral Monuments of the Later Middle Ages. Part II of the O’Tunney Atelier. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland, Vol. 101, No. 1, Pp 25-28. http://www.jstor.org

- Time-Life Books (1998). What Life Was Like: In The Realm of Elizabeth. England AD 1533 – 1603. Pp 68-69.